Irak Plateau in South Sinai: Deep in the remote desert of South Sinai, where the sun scorches the sandstone and the wind whispers across empty horizons, archaeologists have made a discovery that defies imagination. It is not a single tomb or a lone inscription. It is something far more extraordinary: a natural rock shelter that humanity never forgot.

For 12,000 years, people came here. They painted on its walls. They built fires in its chambers. They sheltered their families and their livestock. They left their marks in pigment, in stone, in pottery, and in prayer. Now, for the first time, the Um ‘Irak Plateau is speaking. And its voice echoes across millennia.

This is the story of the most important archaeological discovery in Sinai in decades.

Table of Contents

The Astonishing Find: A Shelter Longer Than a Football Field

The discovery came during routine survey work by Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities. The team was documenting a remote desert area. They had no idea what lay ahead.

Then they found the wall.

A natural sandstone rock shelter stretches for more than 100 meters—longer than a football field—along the eastern side of the plateau. Its overhanging ceiling provided shade and protection. Its floor offered space for habitation. Its walls became canvases.

What the team found inside is nothing short of revolutionary.

What the Paintings Reveal: Art Across 10,000 Years

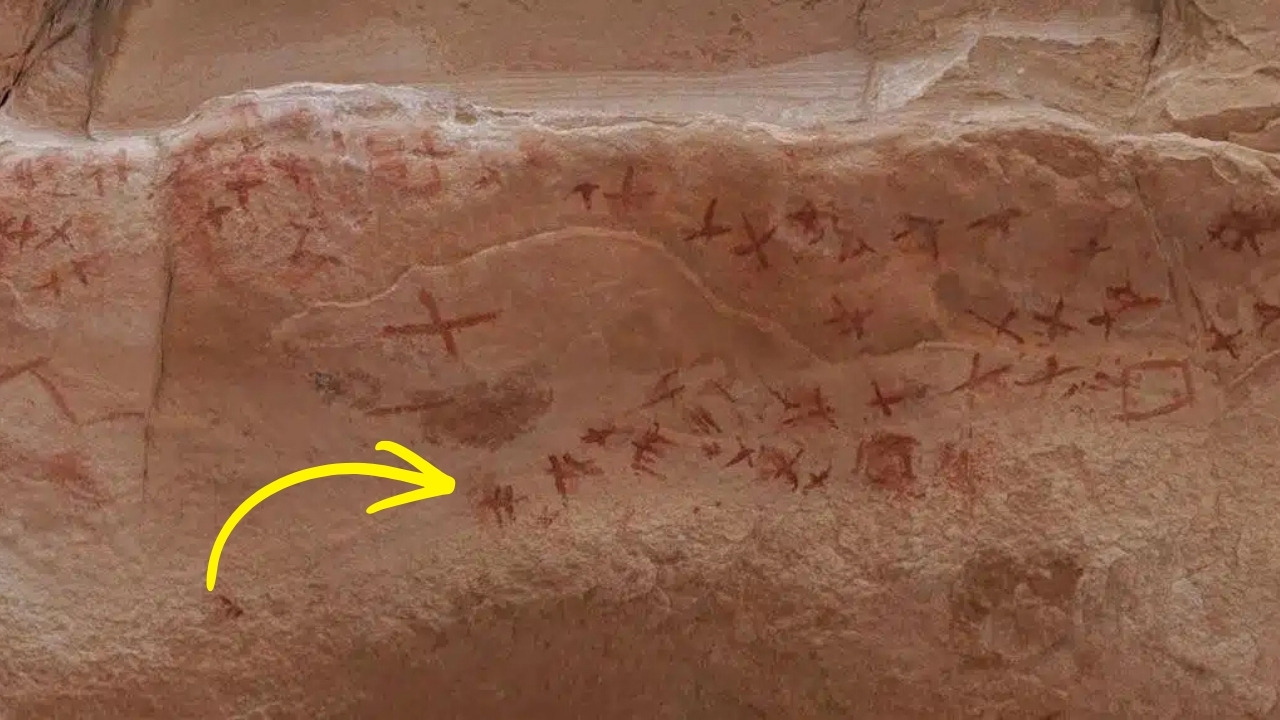

The ceiling of the shelter is covered in paintings. Red pigment, applied by human hands thousands of years ago, depicts animals and symbolic forms. Researchers tentatively date these images to between 10,000 and 5,500 BC. These are among the oldest known artistic expressions in the region.

But the art does not stop there.

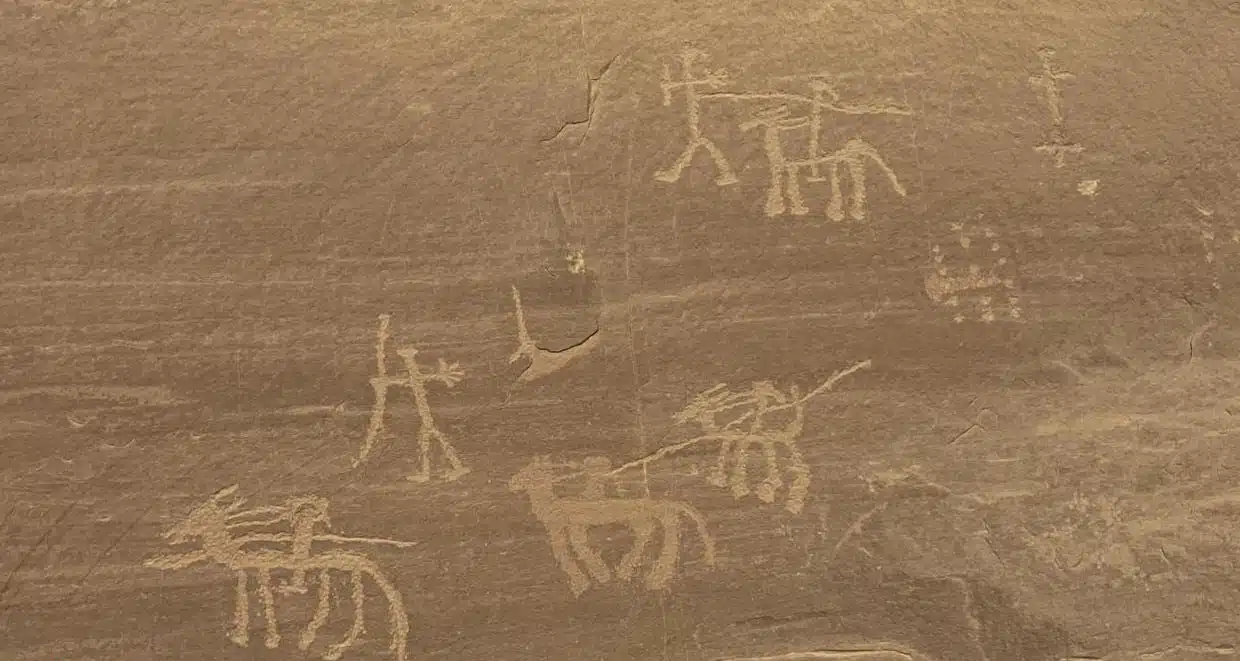

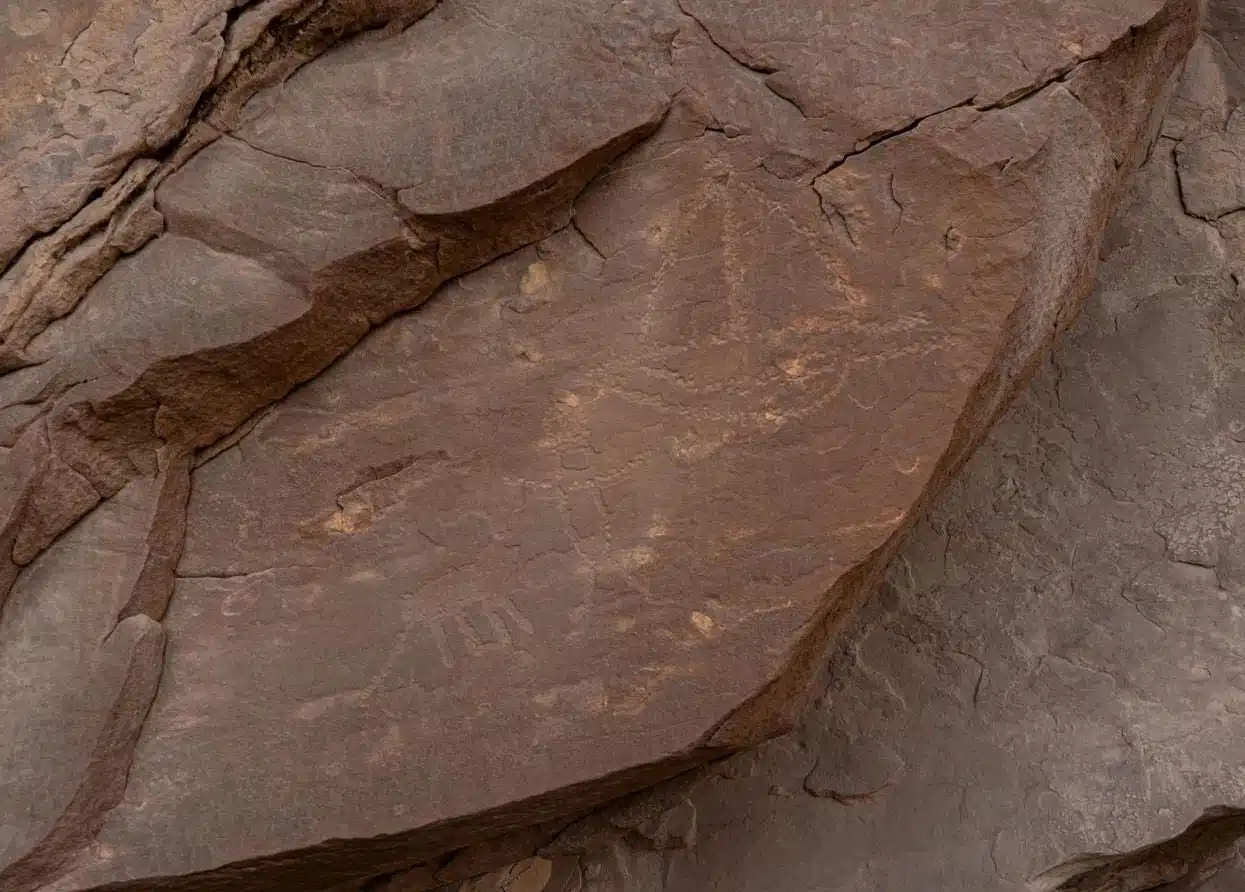

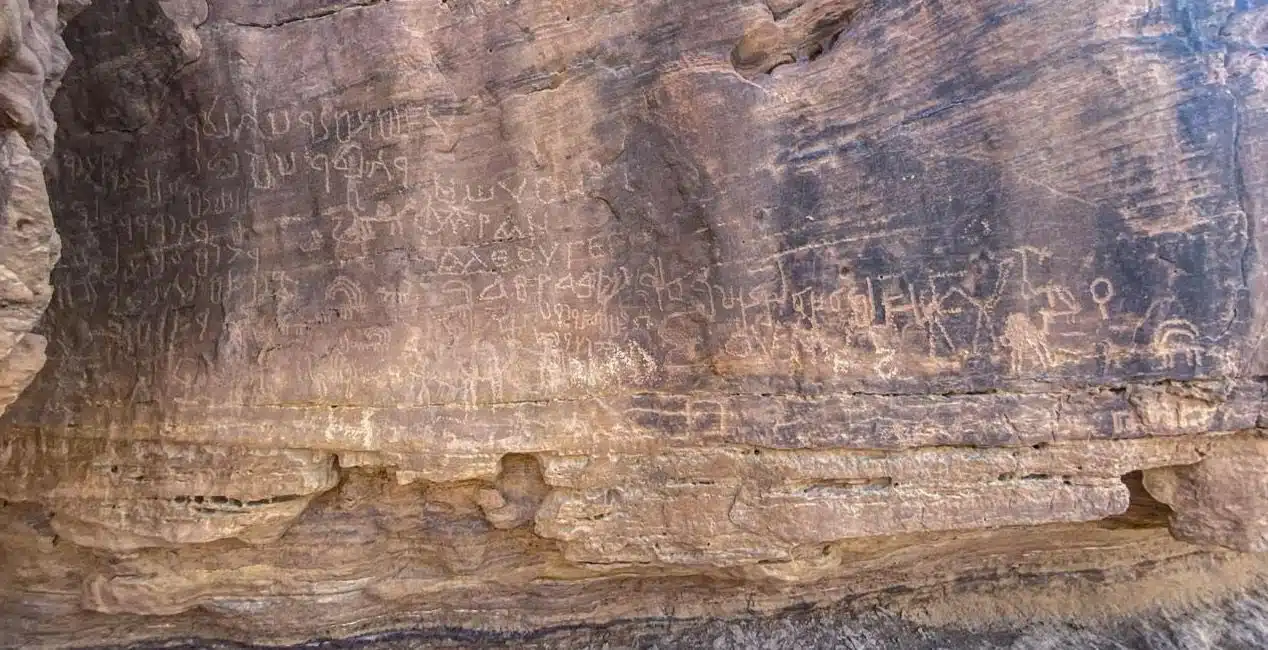

Archaeologists documented a separate group of drawings made in gray pigment, recorded here for the first time anywhere. Shallow relief engravings show hunting scenes—archers pursuing ibex, accompanied by dogs. The compositions are dynamic. They capture movement, skill, and the daily struggle for survival.

These images are not mere decoration. They are records of life.

They show what people valued, what they feared, what they celebrated. The hunters, the ibex, the dogs—these were the realities of existence in prehistoric Sinai. The artists who carved them into stone were telling their own stories, preserving their world for posterity.

Evidence of Long-Term Occupation: A Home for Millennia

The paintings alone would make this site significant. But the Um ‘Irak Plateau offers far more.

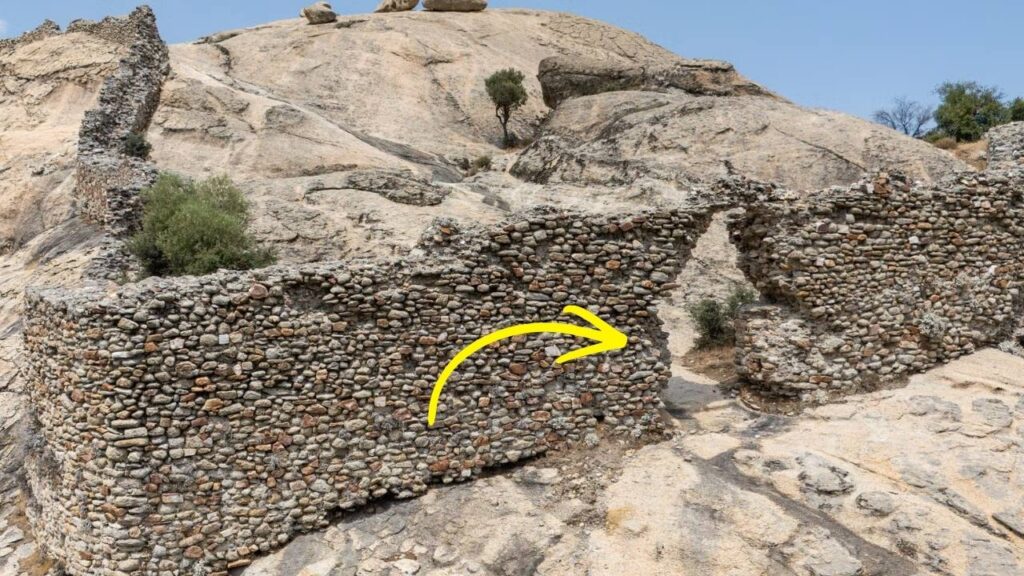

Inside the shelter, archaeologists found clear signs of repeated human use. Stone partitions divide the space into separate living areas. At the center of several compartments, layers of ash and charcoal mark ancient hearths. Fires burned here, generation after generation.

The floor holds animal droppings, thickly deposited. Later inhabitants used the shelter not only for themselves but for their livestock. They adapted the space for survival, seeking protection from rain, wind, and the bitter cold of desert nights.

This was not a temporary campsite. This was a home.

What the Artifacts Reveal: Pottery Across Empires

Survey work across the plateau yielded flint tools and pottery sherds in staggering numbers. The ceramics tell a story of continuous occupation spanning major eras of Egyptian history.

Some fragments date to Egypt’s Middle Kingdom (circa 2055–1650 BCE). Others belong to the Roman period, including examples from the third century AD. The site was not abandoned when the pharaohs fell. It remained in use, adapting to new rulers, new cultures, new worlds.

Later carvings depict camels and horses. Armed riders appear alongside Nabataean inscriptions, pointing to periods of trade and cultural exchange. The Nabataeans, master traders of the ancient world, left their mark here. Arabic inscriptions provide evidence of continued use during early Islamic periods and beyond.

The shelter became a palimpsest—a surface written upon again and again, each generation adding its own chapter.

Global Implications: Sinai as a Crossroads of Civilizations

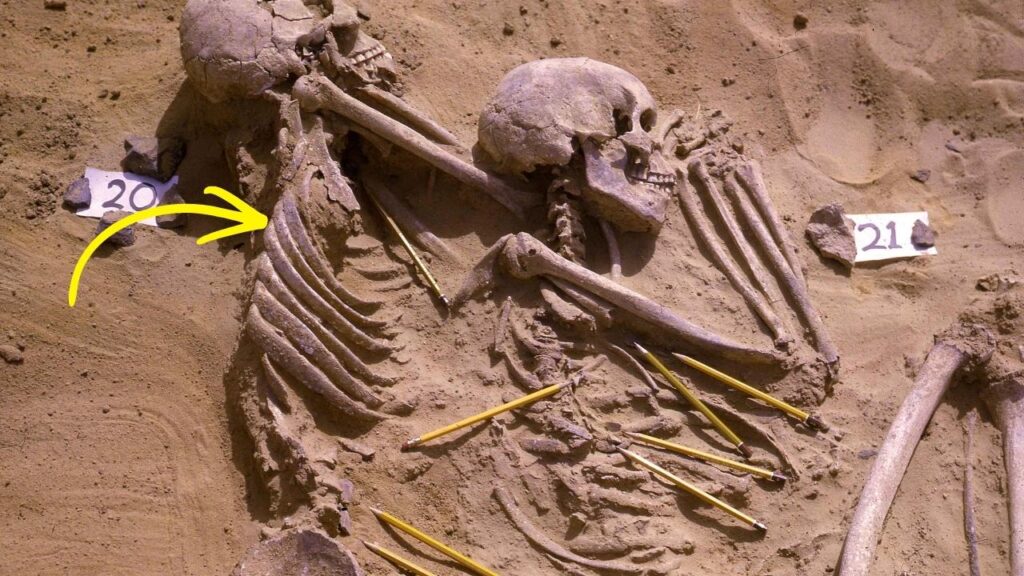

The Um ‘Irak Plateau lies approximately 5 kilometers northeast of the Temple of Serabit el-Khadim, near ancient copper and turquoise mines. Its elevated position overlooks a wide expanse stretching north toward the Tih Plateau. This was not a random gathering place. It was strategic.

Researchers believe the plateau served multiple roles over time: a lookout point, a gathering place, a rest stop for travelers moving through the region. Its location along ancient mining routes made it a natural hub. People passed through. Some stayed. Many left their names, their prayers, their art.

This discovery transforms our understanding of Sinai. The peninsula was not merely a corridor between Africa and Asia. It was a destination, a place where people lived, worked, and expressed themselves for over ten millennia.

Egypt’s Minister of Tourism and Antiquities, Sherif Fathy, described the find as a major addition to Egypt’s archaeological record. It strengthens understanding of Sinai’s role as a crossroads of civilizations. It also enhances Egypt’s position on the global cultural tourism map.

What This Means for History: An Open-Air Museum of Human Expression

Hisham El-Leithy, secretary-general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, called the plateau one of the most important rock art sites identified in recent years. The wide range of artistic styles and inscriptions transforms the site into an open-air museum documenting the evolution of human expression from prehistoric times through the Islamic periods.

This is not hyperbole. The site preserves:

- Prehistoric paintings from 10,000–5,500 BC

- Hunting scenes in shallow relief

- Middle Kingdom pottery

- Roman-era ceramics

- Nabataean inscriptions

- Early Islamic Arabic texts

Each layer adds depth to our understanding of human history. Each mark on the wall represents a moment of connection—between artist and material, between individual and community, between past and future.

The Path Forward: Preservation and Community

Mohamed Abdel-Badei emphasized that the discovery is part of ongoing efforts to survey and document rock art across South Sinai. Local cooperation plays a key role. Residents of the Serabit el-Khadim area have supported the work, helping protect cultural heritage that belongs to all humanity.

Further scientific analysis is underway. Researchers aim to refine dating, study artistic techniques, and develop a long-term preservation plan. The Um ‘Irak Plateau must be protected for future generations. Its walls hold stories that cannot be replaced.

Twelve thousand years of human history, preserved in a single shelter. The people who painted those walls could never have imagined that their marks would endure so long. They could not have known that one day, archaeologists would stand where they stood, tracing their lines with wonder.

But they must have hoped. Why else would they have bothered?

They painted for themselves, for their communities, for the spirits they honored. But they also painted for us. They reached across time, leaving messages in red pigment and shallow relief. And now, at last, we are reading them.

In-Depth FAQs: Your Questions Answered

1. How old are the oldest paintings at Um ‘Irak?Researchers tentatively date the earliest red-pigment paintings to between 10,000 and 5,500 BC. This places them in the Epipaleolithic period, a transitional era when hunter-gatherer societies in the region began developing more complex social structures and artistic traditions. Further analysis may refine this dating.

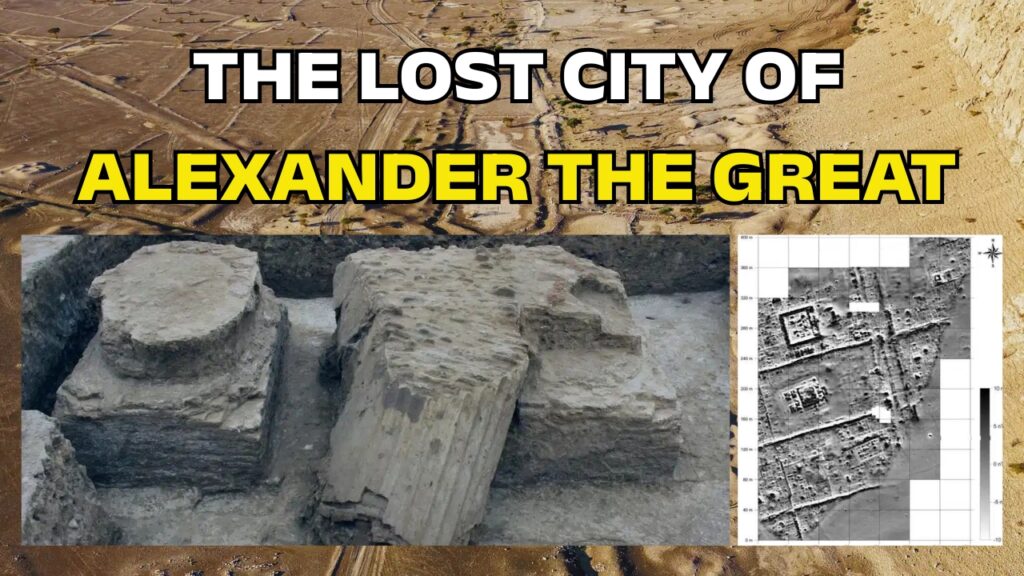

2. What do the hunting scenes show?The shallow relief engravings depict hunters using bows to pursue ibex, accompanied by hunting dogs. These scenes provide direct evidence of hunting techniques, social organization, and the relationship between humans and animals in prehistoric Sinai. The dynamic compositions suggest skilled observation of animal behavior.

3. Who were the Nabataeans, and why are their inscriptions here?The Nabataeans were an ancient Arab people who controlled trade networks across the Arabian Peninsula and Levant from roughly the 4th century BCE to the 2nd century CE. Their capital was Petra in modern Jordan. Their inscriptions at Um ‘Irak indicate that the site lay along or near their trade routes, serving as a waypoint for caravans moving through Sinai.

4. Why was this site used for so long?The natural rock shelter offered essential protection from harsh environmental conditions—rain, wind, and cold. Its location near ancient mining routes and overlooking a wide area made it strategically valuable. The availability of water sources, now possibly dried, would have supported repeated occupation. Each culture that passed through recognized its utility and significance.

5. What happens to the site now?The Supreme Council of Antiquities, in collaboration with researchers, is developing a long-term preservation and documentation plan. Further scientific analysis will refine dating and study artistic techniques. Community involvement with local residents will help protect the site. There is potential for the Um ‘Irak Plateau to become a protected archaeological park, showcasing Sinai’s unparalleled heritage as a crossroads of civilizations.