Imagine a world without a single leaf being eaten. For millions of years after plants crawled onto land, no vertebrate dared to take a bite. The lush Carboniferous forests stretched toward the sun, untouched by grazing mouths. Then, something changed.

Deep in a fossilized tree stump on the cliffs of Nova Scotia, paleontologists have found the proof. A chunky, four-legged creature the size of a football has forced a complete rethink of one of evolution’s most practical questions: when did land animals first develop a taste for plants?

The answer, based on a 307-million-year-old skull, is far earlier than any textbook predicted. This is the story of Tyrannoroter heberti—the pioneer that put plants on the menu.

Table of Contents

The Astonishing Find: A Skull in a Stump

The discovery reads like a paleontologist’s dream. Avocational fossil hunter Brian Hebert was exploring the treacherous cliffs of Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. The site is brutal. Extreme tidal shifts expose fossils only briefly. Researchers must race against incoming waves, grabbing what they can before the sea reclaims it.

Hebert spotted something extraordinary inside a fossilized tree stump: a small, heart-shaped skull.

He recognized its importance immediately. He contacted researchers at the Field Museum and the University of Toronto. What followed was a scientific investigation that would take years and deploy some of the most advanced imaging technology available.

The skull belonged to a creature that lived during the Late Carboniferous Period, approximately 307 million years ago. It was a time of vast coal-forming forests, giant insects, and the earliest experiments in terrestrial life. But this animal was unlike anything paleontologists expected to find.

What the CT Scans Revealed: A Mouth Built for Grinding

Led by Dr. Arjan Mann of the Field Museum and Zifang Xiong of the University of Toronto, the research team subjected the skull to high-resolution micro-CT scanning. The images revealed a shocking secret hidden within the bone.

The mouth was jam-packed with teeth.

Rows of robust teeth lined both the lower jaw and the palate—the roof of the mouth. When the animal closed its jaws, these tooth surfaces interlocked like puzzle pieces. This was not the dentition of an insect hunter. This was a grinding machine.

Analysis of tooth wear patterns confirmed the interpretation. Microscopic facets on the teeth showed evidence of shearing and grinding motions. These are the hallmarks of plant processing. The creature was not just sampling the occasional leaf. It was specialized for vegetation.

Dr. Hillary Maddin, a professor of paleontology at Carleton University and the study’s senior author, described the moment of realization:

“We were most excited to see what was hidden inside the mouth of this animal once it was scanned. It was jam packed with a whole additional set of teeth for crushing and grinding food, like plants.”

Tyrannoroter heberti: The Shingleback Skink of the Carboniferous

The researchers named the new species Tyrannoroter heberti. The genus name references the animal’s probable use of its snout for digging. The species name honors Brian Hebert, the discoverer.

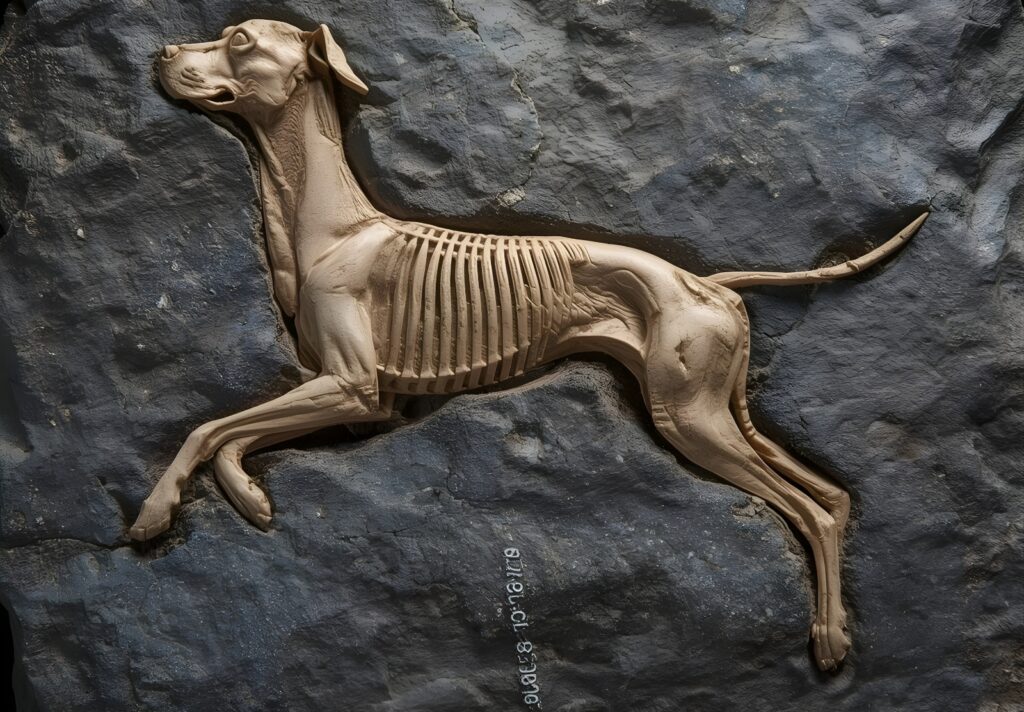

The creature measured roughly one foot in length with a stocky, robust build. Its appearance likely resembled modern shingleback skinks—chunky, slow-moving lizards native to Australia. This body plan suggests a life spent close to the ground, rooting through leaf litter and foraging for food.

But the diet was revolutionary.

While Tyrannoroter likely remained omnivorous, supplementing its meals with insects, the dental specialization points to a significant shift. It had evolved the tools to process tough plant material. This required more than teeth. It likely required a larger gut, microbial symbionts to break down cellulose, and behavioral adaptations to find and select edible vegetation.

Global Implications: Pushing Back the Timeline of Herbivory

The discovery fundamentally revises the timeline for vertebrate herbivory on land. Previous fossil evidence suggested that specialized plant eating emerged primarily among amniotes—the group that includes reptiles, birds, and mammals. Tyrannoroter belongs to a broader category called stem amniotes, animals closely related to the ancestors of all modern land vertebrates but predating the evolutionary split between reptile and mammal lineages.

Dr. Arjan Mann emphasized the significance:

“This shows that experimentation with herbivory goes all the way back to the earliest terrestrial tetrapods.”

The study also examined historical fossils of related pantylid species, finding evidence that similar dental adaptations existed as far back as 318 million years ago. This suggests herbivory became established among these groups relatively quickly after vertebrates became fully terrestrial.

Plants had colonized land roughly 475 million years ago, but vertebrate herbivores appeared much later. The interval between full terrestrial adaptation and the emergence of herbivory now appears substantially shorter than previously estimated.

How Insects Paved the Way for Plants

The researchers note a fascinating evolutionary connection. Hans Sues, senior research geologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and study co-author, has previously observed that nearly all modern herbivores consume some animal protein. The mechanical demands of processing hard insect exoskeletons may have preadapted the dentition for handling tough plant material.

In other words, crunching beetles may have been the evolutionary warm-up for crunching leaves. The robust teeth and powerful jaws needed to break insect armor worked just as well for grinding fibrous vegetation. Once the dental hardware existed, switching to plants became a matter of opportunity.

A Menu That Rewrote Evolution: Multiple Origins of Herbivory

The findings indicate that plant eating evolved independently in multiple groups of early land vertebrates rather than arising once in a common ancestor. The tooth structure in Tyrannoroter differs from that seen in other ancient herbivores, suggesting separate evolutionary trajectories toward the same ecological strategy.

This is a crucial insight. Evolution does not follow a single path. Different lineages, facing similar pressures, arrived at similar solutions through different means. The rise of herbivory was not a single event but a convergent revolution.

What Vanished with the Rainforests

Tyrannoroter lived near the end of the Carboniferous Period, a time of shifting climate. Extensive rainforest ecosystems that covered the tropics began collapsing due to global cooling and drying. This Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse reshaped terrestrial ecosystems.

The researchers note that the lineage containing Tyrannoroter ultimately disappeared, potentially due to inability to adapt as plant communities changed. Many early herbivores specialized on particular plant groups, leaving them vulnerable when those food sources declined.

The transition from the Carboniferous to the subsequent Permian Period involved significant global warming and restructuring of terrestrial ecosystems. The fate of Tyrannoroter offers a data point for understanding how plant-eating animals respond to rapid environmental change—a lesson with modern relevance.

What This Means for History: The Birth of a New World

The appearance of herbivory transformed life on land. Before plant eaters, vegetation grew unchecked, accumulating biomass that would eventually become coal. After herbivores arrived, a new dynamic emerged. Plants evolved defenses. Animals evolved countermeasures. Ecosystems grew more complex.

Tyrannoroter heberti was a pioneer. It lived in a world transitioning from the simple food chains of early terrestrial life to the complex webs we know today. Its teeth, preserved in a tree stump for 307 million years, tell the story of that transition.

The fossil was found by an amateur, in a race against the tide, inside a stump. It is a reminder that discovery can happen anywhere, to anyone, at any time. And it is a reminder that even the smallest creatures can change the course of history.

The first salad eater has finally had its meal acknowledged. Evolution will never look the same.

In-Depth FAQs: Your Questions Answered

1. How do scientists know Tyrannoroter ate plants?The evidence comes from dental morphology and tooth wear analysis. High-resolution CT scans revealed rows of robust, interlocking teeth on both the jaw and palate, designed for grinding. Microscopic wear patterns showed facets consistent with shearing and grinding plant material. This combination of structure and wear is diagnostic of herbivory.

2. Why is this discovery considered a “rewriting” of evolutionary history?Previous evidence suggested specialized plant eating emerged primarily among amniotes (reptiles, birds, and mammals). Tyrannoroter belongs to stem amniotes, a more ancient group predating that split. This pushes the origin of herbivory back by tens of millions of years and shows it evolved independently in multiple lineages.

3. What did Tyrannoroter look like?It was a stocky, four-legged creature about one foot long, resembling modern shingleback skinks. Its robust build and probable digging snout suggest a ground-dwelling lifestyle, foraging through leaf litter for food. It likely maintained an omnivorous diet, supplementing plants with insects.

4. How did the fossil survive for 307 million years?The skull was preserved inside a fossilized tree stump. Rapid burial in sediment, likely during a flood or similar event, protected it from scavengers and weathering. The stump itself became mineralized over time, creating a natural time capsule that preserved delicate bone structure.

5. What happened to Tyrannoroter and its relatives?The lineage disappeared near the end of the Carboniferous Period, during a time of significant climate change. The collapse of vast rainforest ecosystems may have eliminated the specific plants they depended on. Their specialization, an advantage in stable times, became a vulnerability when environments shifted rapidly.