The Shark Hunters of the Desert: Imagine a landscape of arid mountains and parched valleys. The sun beats down relentlessly. Water is scarce. This is southern Arabia today. But 7,000 years ago, something extraordinary was happening here. People were not just surviving. They were thriving. And they were doing it by hunting one of the ocean’s most formidable predators: sharks.

New research from the Archaeological Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences has revealed a stunning truth about Neolithic life in Oman. Excavations at the Wadi Nafūn site show that ancient communities regularly consumed shark meat. This was not a desperate last resort. It was a deliberate, organized, and ritualized practice that sustained generations in one of the planet’s most challenging environments.

This is the story of the shark hunters of the desert.

Table of Contents

The Astonishing Find: A Ritual Site in the Wadi Nafūn

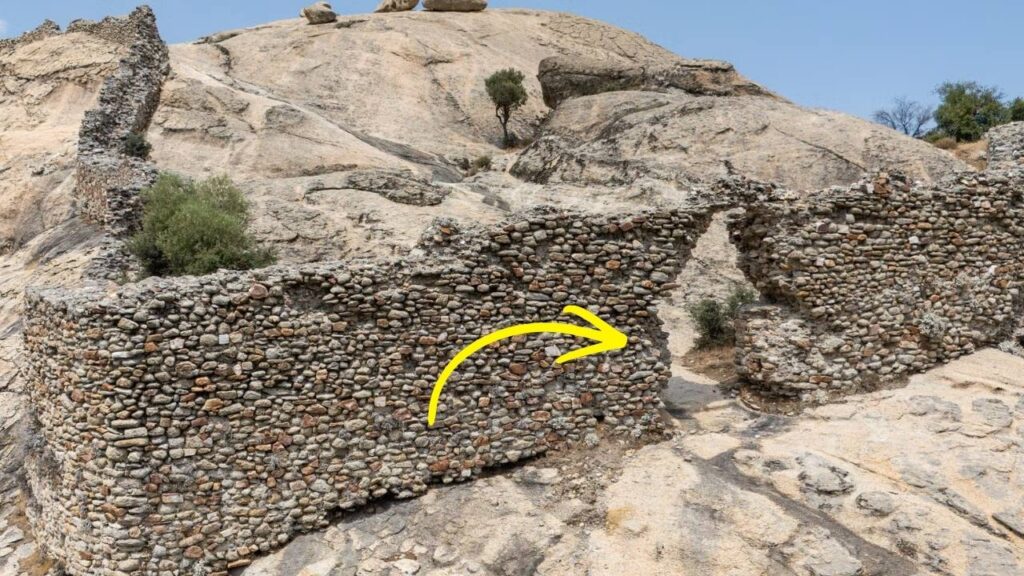

The Wadi Nafūn site lies in the desert region of Oman. For years, archaeologists have recognized its importance. Recent excavations led by the Czech Archaeological Institute have now elevated it to global significance. The site dates to the 5th millennium BCE—roughly 7,000 years ago.

At its heart lies a megalithic tomb.

This was not a simple grave. It was a monumental structure, built to last. Researchers believe it served ritualistic purposes over several centuries. Different communities gathered here repeatedly. They performed ceremonies. They honored their dead. They reinforced social bonds.

Alžběta Danielisová, an archaeologist at the Czech Academy of Sciences, explains the significance:

“This monument was not built by a single small group. It represents cooperation, shared beliefs, and repeated return to a common ceremonial landscape.”

The finding challenges old assumptions. Prehistoric rituals were not just localized affairs. They drew people together across wide areas. The Wadi Nafūn tomb was a hub of Neolithic social life.

What the Teeth Revealed: A Diet of Apex Predators

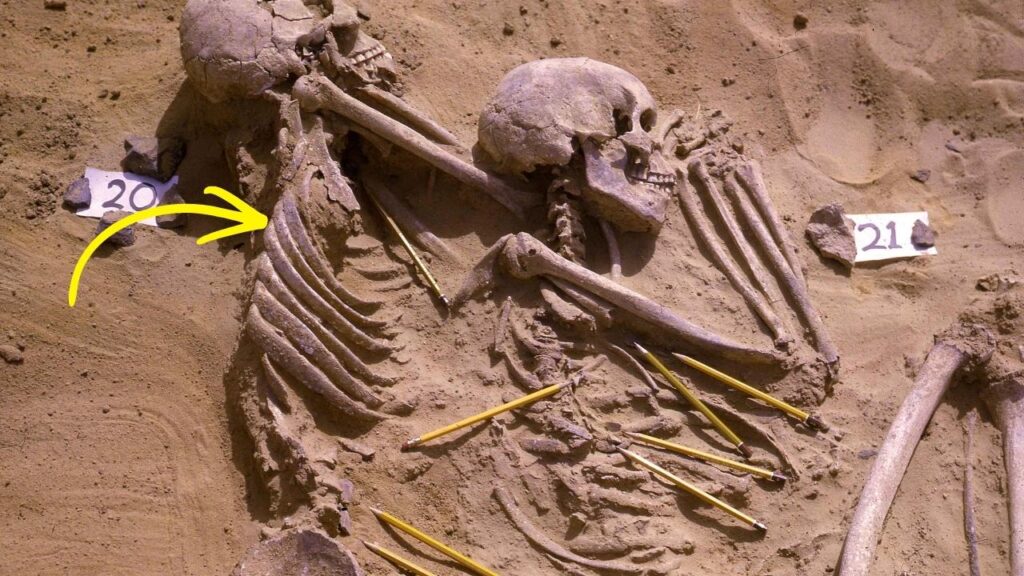

The cultural significance of the site is remarkable. But the most mind-blowing discovery came from an unexpected human teeth.

Scientists analyzed tooth samples from the burials using stable isotope analysis. This technique reconstructs ancient diets by measuring chemical signatures preserved in dental enamel. The results were astonishing.

The isotopic values pointed to regular consumption of marine protein. Not just any marine protein, but protein from the top of the food chain. As Dr. Jiří Šneberger, an anthropologist on the research team, states:

“We are not talking about generic marine protein. These values suggest regular consumption of apex predators, most plausibly sharks.”

Sharks. In the desert. 7,000 years ago.

The implications are staggering. These Neolithic people were not casual fishermen. They were specialized hunters who deliberately targeted the ocean’s most dangerous inhabitants. They developed techniques to catch, process, and transport sharks across significant distances to their inland ritual sites.

Why Sharks? Survival and Nutrition in a Harsh Environment

Southern Arabia 7,000 years ago was not the lush savanna of earlier periods. The climate was arid. Terrestrial food sources were limited. Communities needed reliable, nutrient-dense sustenance.

Sharks provided exactly that.

As apex predators, sharks accumulate high levels of protein and fat. A single large shark could feed many people. Its meat preserved well. Its teeth and bones could be fashioned into tools. No part went to waste.

The regular consumption of sharks indicates a highly organized hunting strategy. These were not opportunistic scavengers picking up dead fish on the shore. They were skilled mariners who ventured into deep waters, armed with knowledge passed down through generations.

This adaptation was crucial for survival. In an unforgiving landscape, access to marine resources made the difference between thriving and perishing.

The Social Meaning: Hunting as a Unifying Force

The Wadi Nafūn discoveries offer more than dietary data. They reveal the social structures of Neolithic communities.

Hunting sharks was not a solitary activity. It required coordination, specialized tools, and collective effort. Boats had to be built. Crews had to be organized. Hunting grounds had to be known. Successful hunts brought prestige and reinforced group identity.

Danielisová emphasizes the ritual dimension:

“This ritualized hunting may have played an important role in unifying different groups within the region, fostering a sense of collective identity and shared purpose.”

The megalithic tomb at Wadi Nafūn becomes even more significant in this context. It was not just a place to bury the dead. It was where hunters gathered, where stories were told, where the community celebrated its relationship with the sea.

Shark hunting and ritual practice were intertwined. They together formed the fabric of Neolithic life.

The Technology: How Did They Hunt Sharks?

The research team did not find preserved boats or fishing gear. Organic materials rarely survive for 7,000 years in desert conditions. But the evidence of shark consumption implies the existence of sophisticated maritime technology.

These hunters likely used watercraft capable of navigating coastal waters. They crafted hooks, lines, and perhaps harpoons from bone and wood. They understood shark behavior and seasonal patterns. They knew where to find their prey and how to subdue it.

This level of knowledge did not emerge overnight. It developed over generations, accumulating through trial, error, and shared experience. The shark hunters of Neolithic Arabia were masters of their environment.

Global Implications: Rewriting Neolithic Capabilities

The Wadi Nafūn findings challenge long-held assumptions about prehistoric societies. For decades, the Neolithic was characterized as a time of farming and herding, of settling down and staying put. Coastal resources were acknowledged but rarely emphasized.

This discovery changes that narrative.

It shows that Neolithic communities could be simultaneously terrestrial and maritime. They maintained ritual centers far inland while exploiting rich marine resources. They built monumental architecture while developing advanced hunting techniques. They were not simple villagers. They were complex, adaptive, and connected.

The Arabian Peninsula, often viewed as a marginal environment, emerges as a zone of innovation. People here developed specialized skills that allowed them to thrive where others might have perished. Their success offers lessons in resilience and adaptation.

What This Means for History: The Desert and the Sea

The story of Wadi Nafūn is still unfolding. The Czech team continues its work. More excavations, more analyses, more discoveries lie ahead.

But one thing is already clear. The people of Neolithic Arabia were not isolated survivors clinging to existence. They were shark hunters. They were ritual participants. They were builders of monuments and masters of the sea.

Their descendants may have forgotten their names. But their bones, their teeth, and their tombs preserve their legacy. Seven thousand years later, we are finally learning to read it.

The desert holds many secrets. Some lie beneath the sand. Others wait in the sea. At Wadi Nafūn, the two meet. And history is rewritten.

In-Depth FAQs: Your Questions Answered

1. How can scientists tell that these ancient people ate sharks?Researchers used stable isotope analysis on human tooth enamel. This technique measures ratios of different forms of carbon and nitrogen, which vary depending on what a person ate. The isotopic values at Wadi Nafūn were unusually high, consistent with regular consumption of apex marine predators. Among the most likely candidates in the region are sharks, which occupy the top of the marine food chain and concentrate heavy isotopes in their tissues.

2. Where were these Neolithic communities getting sharks if they lived in the desert?The Wadi Nafūn site is located inland, but the communities using it likely had access to the Arabian Sea coast, which is not far distant. They would have traveled to the coast to hunt, then transported processed shark meat back to their ritual centers. This indicates organized logistics and trade networks within and between groups.

3. What kind of sharks were they hunting?The study did not identify specific shark species, as the analysis was on human teeth rather than shark remains. However, the waters off southern Arabia are home to a variety of sharks, including tiger sharks, bull sharks, and various requiem sharks. All are large, powerful, and would have provided substantial meat and resources.

4. How did Neolithic people hunt sharks without modern technology?While no direct evidence of hunting gear survived, researchers infer the use of watercraft, hooks, lines, and possibly harpoons made from bone, wood, and stone. These techniques are documented ethnographically in various coastal societies. Hunting sharks would have required knowledge of their behavior, seasonal movements, and breeding grounds—knowledge accumulated over generations.

5. What does this discovery tell us about Neolithic social organization?The evidence points to complex, interconnected communities capable of organizing specialized hunting expeditions and maintaining long-distance ritual centers. The megalithic tomb at Wadi Nafūn required cooperative labor and shared beliefs. The shark hunting required specialized skills and coordinated effort. Together, they paint a picture of societies far more sophisticated than the simple “farmers and herders” model traditionally applied to the Neolithic.