The Lost City of Alexander the Great: For over a millennium, it slept beneath the sand. A ghost city founded by history’s greatest conqueror, erased by floods, rebuilt by kings, and eventually swallowed by the desert. Its name appeared in ancient texts. Its location remained a mystery. Until now.

Deep in modern-day Iraq, archaeologists have finally uncovered the remains of Charax Spasinou—one of the last cities ever founded by Alexander the Great. The discovery, made possible by drones and advanced imaging technology, is rewriting our understanding of Alexander’s legacy and the ancient world’s trade networks.

This is the story of a city lost for 1,200 years, and the technology that brought it back.

Table of Contents

The Astonishing Find: Alexander’s Final Vision

The year was 324 BCE. Alexander the Great was at the zenith of his power. His armies had swept across Persia. Egypt had fallen. The known world lay at his feet. During this final chapter of his life, he ordered the foundation of a new city at a strategic location.

It would be called Alexandria.

But not the famous Alexandria in Egypt. This was Alexandria-on-the-Tigris, established in what is now southern Iraq. Alexander populated it with veteran soldiers and settlers from a destroyed nearby town. It was meant to be a stronghold, a trading hub, a beacon of Greek culture in Mesopotamia.

Then, just one year later, Alexander died in Babylon at age 32. He never saw his city flourish.

The city’s fate became entangled in history. Pliny the Elder recorded its turbulent story. The original Alexandria was destroyed by floods. A Seleucid king named Antiochus rebuilt it, renaming it Antioch. More floods came. Finally, a local ruler named Spaosines restored it once more, building massive embankments to tame the rivers. He gave it his own name: Charax Spasinou.

The city survived for centuries. It became a wealthy trading hub. And then, it vanished.

The Century-Long Hunt: Where Was Alexander’s City?

For generations, historians and archaeologists debated its location. They had Pliny’s description: a city on an artificial elevation, between the Tigris and another river, at their junction. But rivers change course. Landscapes shift. The precise spot remained elusive.

In the 1960s, a British researcher named John Hansman examined Royal Air Force aerial photographs. He spotted something intriguing: a huge walled enclosure and traces of settlement in the region. It was a promising lead. But he could not follow it.

Geopolitics intervened.

Decades of conflict in Iraq made on-the-ground research impossible. The site, whatever and wherever it was, remained out of reach. The lost city waited.

How Drones and Magnetometers Finally Solved the Mystery

In 2014, conditions finally allowed access. A research team moved in to conduct large-scale surface surveys. They walked across more than 500 square kilometers. They recorded dense scatters of pottery, brick fragments, and industrial debris. The surface was speaking. They were listening.

Then came the drones.

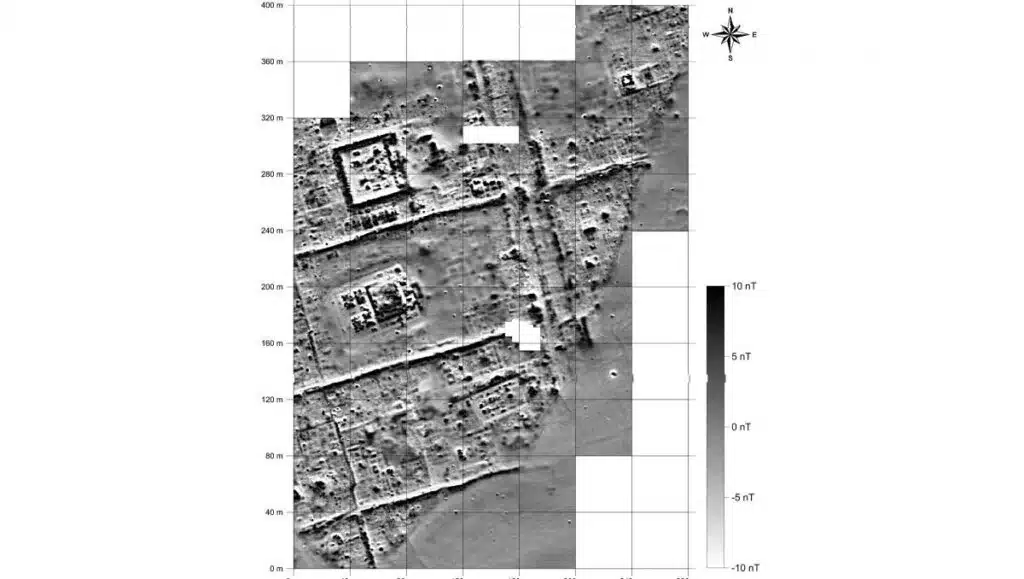

Thousands of aerial photographs built a detailed terrain model. Every bump and shadow was mapped. Next, geophysicists deployed magnetometers. These instruments measure subtle variations in the Earth’s magnetic field. Buried walls, kilns, and foundations distort that field. The magnetometers revealed what lay beneath.

The results were nothing short of revolutionary.

A complete city emerged from the data. Wide streets formed a grid. Large housing blocks stretched across the urban plan. Some of these house blocks were of exceptional size—larger than most known from other cities of the same era. This suggests Charax Spasinou was not just another provincial town. It was a place of wealth and importance.

Temple compounds sat within walled precincts. Workshops with kilns indicated industrial activity. Canals connected to the river. Harbor basins marked the waterfront. The city was designed for movement, for exchange, for prosperity.

What the City Reveals: A Commercial Powerhouse

Charax Spasinou’s location was strategic. It sat at the meeting point of the Tigris and Eulaeus rivers, at a crossroads of ancient trade routes. Goods from the Persian Gulf could move upriver. Caravans from Arabia could reach its markets. Products from the Mediterranean could flow through.

This was a hub of commerce.

The newly revealed street grid and harbor infrastructure confirm its economic importance. The presence of workshops and kilns points to local production. Merchants likely exchanged textiles, metals, spices, and luxury goods within its walls. The city connected Mesopotamia to the Hellenistic world and beyond.

Its prosperity attracted attention. When the Parthian Empire rose, they took control. When the Romans pushed east, they coveted it. Charax Spasinou sat at the intersection of empires, surviving through adaptation and resilience.

The District of Giants: Exceptionally Large House Blocks

One detail stands out. The magnetic survey revealed a district containing house blocks of exceptional size. These were not ordinary dwellings. They were larger than most known from other cities of the same era.

What does this mean?

Possibly the residences of elite merchants or administrators. Possibly public buildings or storage facilities. Possibly evidence of a social structure different from other Hellenistic cities. The size alone signals wealth and status. Whoever lived or worked there commanded resources.

Further excavation may reveal the answer. For now, the giant house blocks remain a tantalizing mystery.

Global Implications: A New Window into Alexander’s Legacy

This discovery transforms our understanding of Alexander’s final years. He founded dozens of cities across his empire. Most bore his name. But Charax Spasinou was among the last. It represents his vision for integrating conquered territories into a unified economic and cultural network.

The city also illuminates the post-Alexander world. After his death, his generals carved up the empire. The Seleucids ruled Mesopotamia. They rebuilt and renamed cities, adapting Alexander’s foundations to their own needs. Charax Spasinou reflects this continuity and change.

The harbor and trade connections reveal the economic vitality of the region. The pottery scatters spanning centuries show long-term occupation. The city did not die with its founder. It thrived, adapted, and eventually faded as the rivers shifted and the trade routes changed.

What This Means for History: Excavations Await

For now, Charax Spasinou remains buried. The surveys have mapped it. The mystery of its location is solved. But the real work is just beginning.

The research team hopes to secure permission for full-scale excavations. They want to uncover the streets, the temples, the homes of Alexander’s veterans. They want to walk where Spaosines built his embankments. They want to touch the bricks of a city that rose from floods and survived for centuries.

The drone photographs and magnetometer data provide a roadmap. Every buried wall is marked. Every potential trench is planned. When excavations begin, they will proceed with precision.

Charax Spasinou is one of Alexander’s last works. It was founded as he raced toward the end of his life. It witnessed the rise and fall of empires. It was lost, and now it is found.

The desert kept its secret for 1,200 years. Not anymore.

In-Depth FAQs: Your Questions Answered

1. How was Charax Spasinou finally located after centuries of searching?The breakthrough came from a combination of non-invasive survey techniques. Researchers conducted extensive surface walking to collect pottery and debris. They used drone photography to create high-resolution terrain models. Most importantly, they deployed magnetometers, which detect buried structures by measuring magnetic field distortions. This multi-layered approach revealed the city’s grid, buildings, and infrastructure without digging a single shovel.

2. Why does the city have multiple names?Each name marks a distinct phase in its history. Alexandria was the original name given by Alexander the Great in 324 BCE. After destruction by floods, the Seleucid king Antiochus rebuilt it and renamed it Antioch. Following another flood, the local ruler Spaosines restored it once more, built protective embankments, and renamed it Charax Spasinou—”Charax” meaning fortress or enclosure, and “Spasinou” referring to Spaosines himself.

3. What role did Pliny the Elder play in finding the city?Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia, written in the first century CE, provided the essential literary description of the city’s location. He placed it on an artificial mound between the Tigris and Eulaeus rivers at their junction. While not precise enough for GPS coordinates, his account gave researchers a general region to investigate and confirmed the city’s historical existence and significance.

4. Why are some house blocks described as “exceptionally large”?The magnetometer survey revealed a district with house blocks larger than most known from other cities of the same era. This suggests the presence of elite residences, public buildings, or specialized storage facilities. The size indicates wealth and importance, though the exact function awaits confirmation through future excavation.

5. Will archaeologists actually dig up the city?The research team hopes to conduct future excavations pending permits and funding. The drone and magnetometer surveys have provided a detailed map of what lies beneath. Excavations would allow archaeologists to recover artifacts, date construction phases, and understand daily life in the city. For now, the site is protected and documented, awaiting the next phase of discovery.