Beauty leaves traces. Sometimes, those traces last for millennia. Archaeologists at the Dong Xa site in northern Vietnam have uncovered the oldest direct evidence of a striking tradition—intentional tooth blackening. The teeth, dating to around 2,000 years ago, carry chemical fingerprints of a deliberate, meticulous cosmetic practice. This discovery connects Iron Age communities with living memory. It reveals a continuous thread of cultural identity woven through two millennia of Vietnamese history.

The blackened smile was not a flaw. It was a mark of beauty, maturity, and belonging.

Table of Contents

The Astonishing Find: Chemistry Confirms Culture

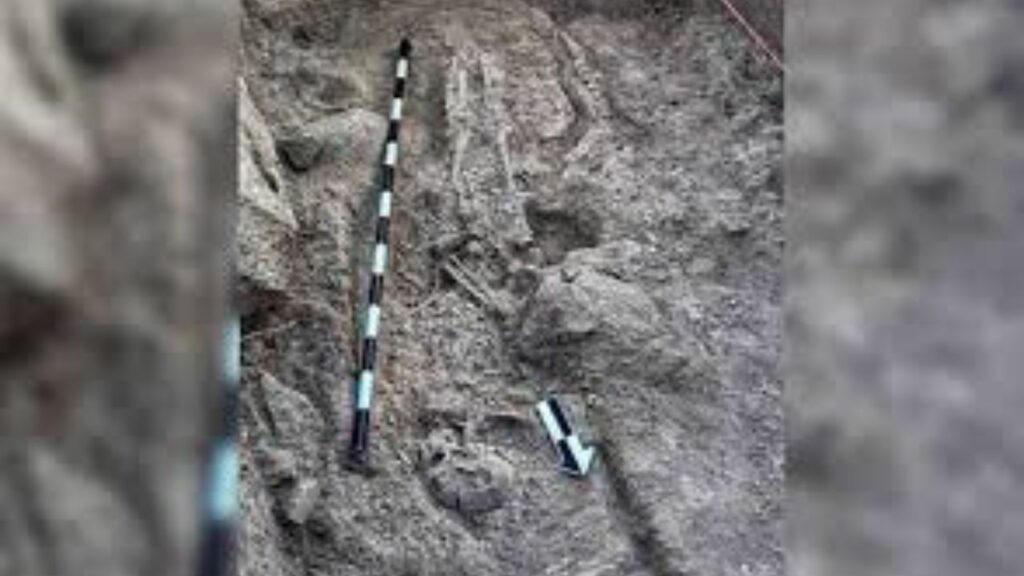

For decades, archaeologists encountering darkened teeth in ancient burials faced a puzzle. Was it diet? Betel chewing leaves deep red stains. Was it simply the effect of burial soil? The Dong Xa team needed certainty. They turned to advanced chemical analysis to find the truth.

The results were electrifying.

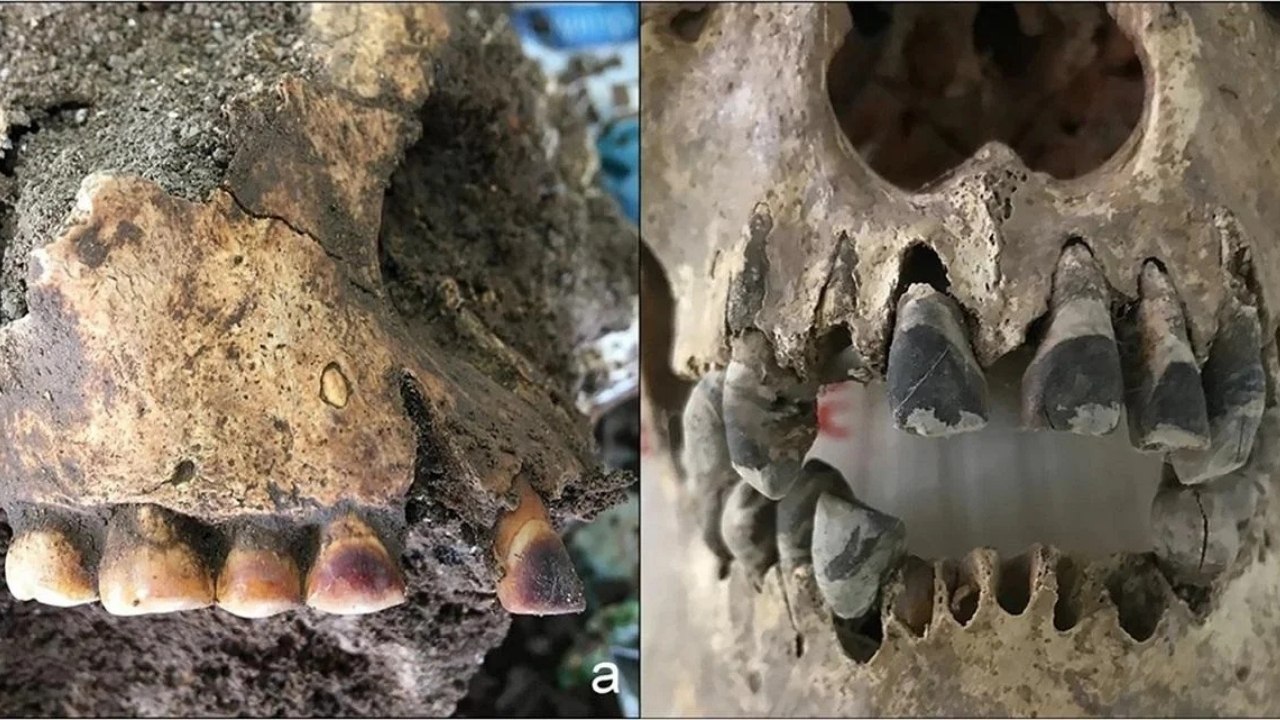

Researchers extracted microscopic samples from the teeth of three individuals. Using scanning electron microscopy and portable X-ray fluorescence, they measured the elemental composition without damaging the precious remains. The enamel revealed a distinct chemical signature: high levels of iron and sulfur. This specific combination does not occur naturally. It does not come from betel. It comes from a recipe.

What the Artifacts Reveal: The Science of a Ritual

The chemical duo tells a clear story. Iron salts mixed with tannin-rich plants create iron tannate compounds. These compounds produce a deep, permanent black color. They are chemically similar to iron gall ink, the standard writing ink used in Europe for centuries.

To confirm their theory, the team recreated history.

They formulated a staining mixture based on ethnographic records—likely using iron from natural sources and tannins from local plants. They applied it to a modern animal tooth. The experimental result was a perfect match. The same elevated iron and sulfur appeared. The same glossy, dark surface emerged. The Dong Xa individuals underwent a deliberate, controlled process. They chose to transform their appearance.

This was not accidental staining. This was a rite.

Connecting to the Dong Son World

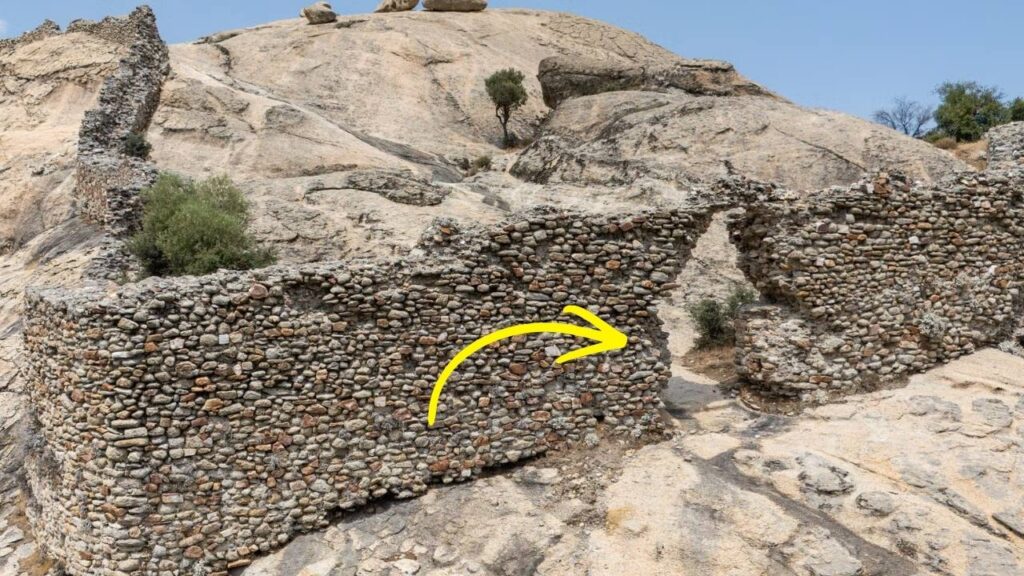

The burial context places these individuals within the Dong Son cultural complex. This was a sophisticated Iron Age society, famed for its magnificent bronze drums, intricate weapons, and far-reaching trade networks across mainland Southeast Asia. These were people of power and artistry.

Until now, our understanding of Dong Son appearance came largely from bronze artifacts. Those cast images depict warriors in feathered headdresses, bodies marked with tattoos. The Dong Xa discovery adds a vivid new dimension. These ancient people also modified their most visible feature—their smiles. Blackened teeth completed the portrait of a cultured, adorned individual.

Global Implications: A Tradition Two Millennia in the Making

The significance of this find extends far beyond a single site. It pushes the documented history of Vietnamese tooth blackening back by approximately 2,000 years. This practice was not a fleeting fashion. It was a deeply rooted cultural value, persisting from the Iron Age through French colonialism and into the twentieth century.

Historical accounts describe the methods in rich detail.

Some practitioners rubbed their teeth with tannin-rich plants or soot from burned coconut shells. Others followed an elaborate, multi-week process using iron-based mixtures that produced a glossy, lacquer-like finish. By the early 1900s, diverse ethnic groups across Vietnam embraced the practice. It transcended region and social class. It was a unifying marker of Vietnamese identity.

What This Means for History: Separating Intent from Accident

The Dong Xa study provides archaeologists with a powerful new tool. The elemental signature of iron and sulfur offers a clear, verifiable method for distinguishing intentional staining from natural discoloration. This will transform future research across Southeast Asia and beyond.

Many cultures practiced tooth modification.

In Japan, ohaguro darkened the teeth of married women and samurai. In parts of Indonesia, similar traditions existed. In prehistoric Taiwan and the Philippines, teeth were intentionally filed and sometimes blackened. Now, researchers have a chemical blueprint to identify these practices with confidence, even when historical records are silent.

The teeth from Dong Xa bridge two worlds. They connect the Iron Age with the living memory of Vietnamese elders photographed in the early 1900s, their smiles gleaming ebony. They remind us that beauty is not universal. It is cultural, deliberate, and deeply meaningful. For two thousand years, the people of Vietnam looked at blackened teeth and saw something precious—identity, maturity, and belonging.

The ebony smile endures, not on living faces, but in the archaeological record. And now, thanks to science, we finally understand its message.

In-Depth FAQs: Your Questions Answered

1. How can scientists tell the difference between betel staining and intentional blackening?Betel chewing leaves reddish-brown stains composed primarily of organic compounds. Intentional tooth blackening using iron-based mixtures leaves a distinct elemental signature—specifically, elevated levels of iron and sulfur that form stable, dark iron tannate compounds. These elements are detectable through X-ray fluorescence and electron microscopy, even after thousands of years.

2. Why did people in Vietnam blacken their teeth?Tooth blackening served multiple purposes. It was a mark of beauty and maturity, distinguishing adults from children. It also signified cultural identity and social belonging. Some accounts suggest it protected teeth from decay, though this was likely a secondary benefit. The practice communicated that an individual was civilized, married, and fully integrated into society.

3. How long did the tooth blackening process take?Ethnographic records describe a multi-stage process lasting approximately 20 days. The initial applications involved acidic or astringent plant substances to clean and prepare the enamel. Subsequent applications of iron-rich mixtures built up the color gradually. The final result was a deep, glossy black surface considered highly attractive.

4. Was this practice unique to Vietnam?No. Various forms of tooth modification appear across the globe. In Japan, ohaguro blackened the teeth of aristocrats and married women. In parts of Southeast Asia and the Pacific, tooth filing and blackening were common. In prehistoric Taiwan and the Philippines, archaeologists have found teeth with evidence of intentional filing and pigment application. The Vietnamese tradition is notable for its remarkable longevity and cultural continuity.

5. Do any communities still practice tooth blackening today?The practice has largely died out in Vietnam and most of East Asia, particularly under the influence of Western beauty standards during the colonial period and after. However, isolated communities in Southeast Asia, the Andaman Islands, and parts of Africa continue related traditions. The chemical methods developed in this study may help identify surviving practices and protect this intangible cultural heritage for future generations.